La Posada included plans not only for the hotel building but also for 12 acres of gardens based on sustainable desert plant communities.

Gardens at La Posada Hotel

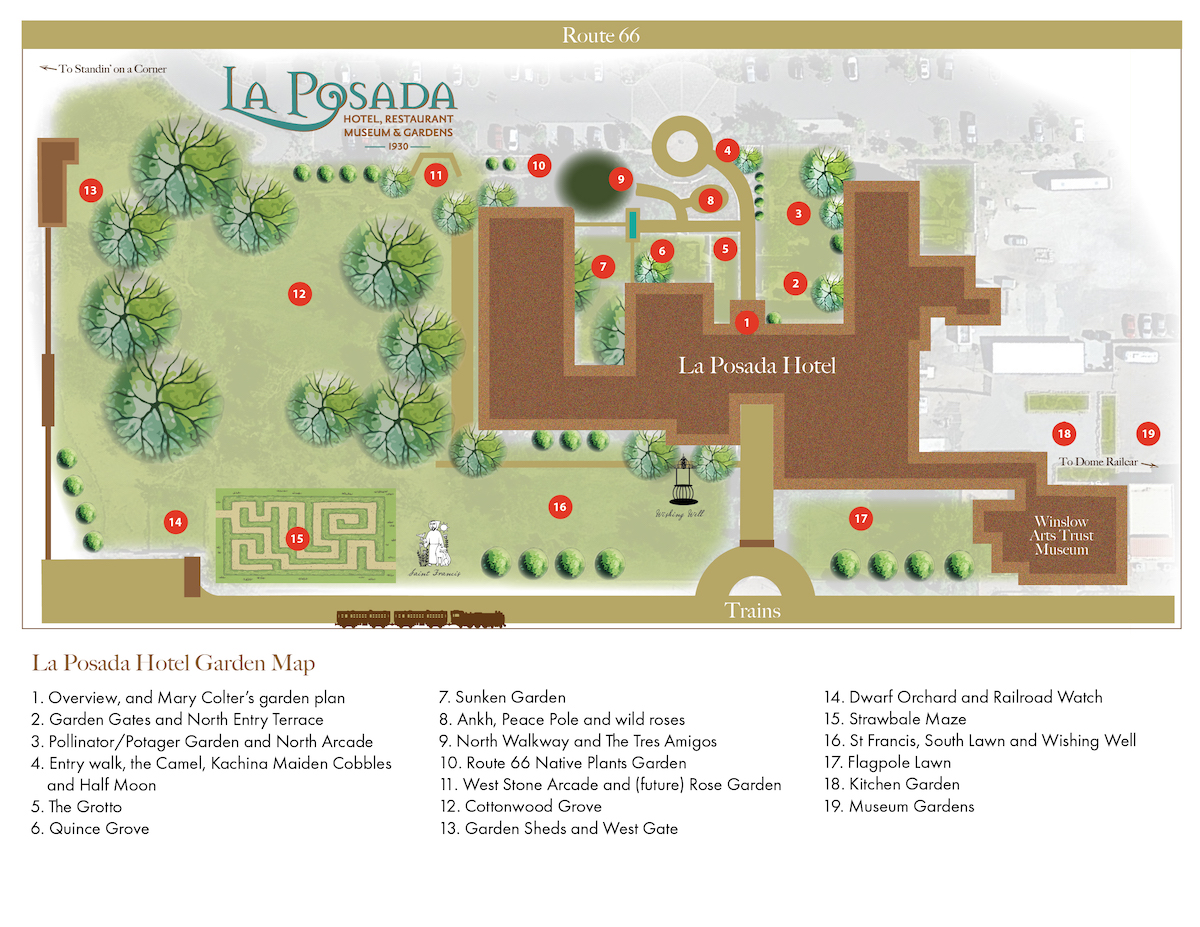

Mary Colter’s original 1930 design for La Posada included plans not only for the hotel building but also for 12 acres of gardens based on sustainable desert plant communities. Unfortunately, these plans were never implemented because the Santa Fe Railway faced major budgetary constraints in the years following the Great Depression. By the 1980s, La Posada’s gardens had fallen into total disrepair.

We started restoring La Posada in 1997 and the gardens have been under continuous improvement since then. The Sunken Garden has been restored, and the Rose and Potager Gardens are thriving on the north side. The Cottonwood Grove has been stabilized and new trees have been planted. The South Lawns are healthy and new walkways and a straw bale maze has been added. To the east, another 5 acres of gardens and a vineyard are planned to surround the Depot and the Turquoise Room restaurant is scheduled to expand into the gardens with patio seating. Construction of these gardens will start in 2012. Colter’s vision of an oasis in the desert has finally been realized. With careful management, La Posada’s gardens will continue to grow and mature for decades to come.

A WALKING TOUR THROUGH LA POSADA’S GARDENS

Click on the items below to read the full description

Begin your tour in the entry hall, in front of Mary Colter’s only known garden plan. Done in 1929, this fascinating concept showed the various areas of an estate garden. In keeping with the fantasy of La Posada as a great family home, the gardens would decrease in formality as you moved farther from the hacienda. As far as we know, no detailed plans for the gardens were ever developed, and most of the planned gardens were never built – during construction of the hotel in 1929 the country slipped into a great economic depression. As banks and railroad companies collapsed, the Santa Fe railway decided not to finish the gardens. We did not know these plans existed until a guest found them in the archives of the Santa Fe Railway in Topeka Kansas.

Note that the hotel entry faced the railroad tracks to the south, not north to Route 66 (now 2nd Street) as it does today. In 1930 the railway assumed most hotel guests would come by train instead of by car. The back door, on Route 66, just had a drop-off for visitors and no parking! There was a little parking area to the east, and no separate parking for staff.

In the 1960’s the Santa Fe Railway converted La Posada into their Arizona division offices. The Route 66 entry gardens were entirely paved for staff parking. When Allan and Tina acquired the rundown property in 1997 the gardens had been abandoned. In 1998 when we found Colter’s original landscape plan we decided to complete the gardens, keeping her basic intent and layout but bringing the plans into current best practices. For example, we are committed to long-term sustainability of the environment and protection of creatures great and small. Our gardens are a Certified Wildlife Habitat. What does that require? A sustainable water supply, in our case with fountains, rain catchment, well irrigation and drip sprinkler system. Food Sources, such as fruits from orchard areas, flowers left to go to seed, bird feeders, and a healthy insect population. Shelter for critters: a variety of trees, shrubs, native plants and flowers. Organic practices to keep everything safe. Providing safe places for: birds, skunks, snakes, mantises, butterflies, etc to procreate. Organic and sustainable practices. No pesticides. Organic remedies & companion planting. Native flowers and perennials blooming from Spring to Fall to encourage pollinator populations. And leaving snags for the healthy raptor population. La Posada is also a recognized Pollinator Habitat. We have many varieties of native and perennial plants, flowers & trees which provide nectar and pollen throughout the growing season. Organic and sustainable gardening protects our pollinators. We maintain woody shrubs, deadwood & snags for protective egg laying, cocoon, and hibernation sites, and we leave the flowers which have gone to seed, and leaves on the beds.

To begin your walking tour of La Posada’s Organic Gardens, please walk outside through the hotel’s north (Route 66) entrance. Recall that during the railroad era, this was the “back side” of the hotel. The tracks and trains were (and still are) located on the hotel’s south side, meaning that guests in those days entered La Posada through the south entrance doors. After walking outside, take an immediate right through the wrought iron gate and stand upon the patio, looking northward towards Route 66. The Painted Desert and the vast, arid interior of the Colorado Plateau stretch into the far distance, northward beyond Route 66 and Interstate 40. You are standing on the southern end of the elevated and eroded Colorado Plateau, down within the narrow bowl of the Little Colorado River Valley. The Little Colorado River begins as snowmelt and rainfall on the Mogollon Rim and White Mountains to the south/southeast of Winslow, and flows northward, passing La Posada just a few miles to the east. Eventually the Little Colorado River meets the “Big” Colorado River near Cameron on the Navajo Nation, north of Flagstaff. Just south of the Mogollon Rim there is a steep escarpment as the Colorado Plateau gives way to the Sonoran Desert, which begins with Phoenix and extends well into Mexico.

We created this garden to separate the hotel environs from the parking area – to create an oasis. There are two things going on here: Pollinator habit and a Potager. Pollinator sightings include a variety of bees, hummingbirds, butterflies, moths & birds. We rely on these busy pollinators for the health of much of what we eat. Great progress has been made in the planting and seeding of Butterfly Milk Weed; you might see Monarch Butterflies on their long migration south. You might also find roses, perennial flowers, China Rose, Blanket Flower, Moonshine Yarrow, Cosmos, Rocky Mountain BeeBalm, Butterfly Milkweed, Bachelor Button, Maximilian Sunflower, Hollyhock, Rudibeckia, and more.

We also use this space as an ornamental kitchen garden (that’s what “Potager” means) to grow edible plants like corn, amaranth, pumpkins, squash, and basil for our award-winning restaurant, The Turquoise Room. We get the Turquoise Room’s vegetables, fruits, and other foods from local and regional farms and gardens, including our own. We followed Colter’s example by using both indigenous and European models to design this garden. The Potager’s circular shape and four main pathways in the sacred four directions honor the cultural traditions of the Hopis and Navajos, whose homelands surround La Posada. Seen from above (or the 2nd floor gallery), the Potager Garden’s layout also echoes the design of the Santa Fe Railroad’s iconic logo.

The kinds of plants that you find growing in the Pollinator/Potager Garden will depend upon the season. If it is summertime, the garden should be green and lush. In winter we usually grow soil-nourishing cover crops and cold-tolerant edible greens, like rainbow chard. During the frost-free growing season (late April to late October), we especially enjoy growing Hopi red amaranth here. This tall, red-flowering plant seems to love this relatively warm, protected space: La Posada’s thick and tall thermal mass shields the Potager Garden from the Colorado Plateau’s strong and dry southwest spring winds, while the warm sunlight absorbed and stored in the hardscape helps keep air temperatures warmer at night. If it is a windy day in springtime, the Potager Garden will be relatively calm and warm, especially compared to other, less protected gardens on the hotel’s south and west side.

On the outer square edges, you will find perennial plants like lavender, “Marshall seedless” ash trees, and both wild and domesticated roses. Lavender is a fragrant, drought-tolerant species of Mediterranean origin; it enjoys Winslow’s aridity (we rarely receive more than eight inches of moisture per year). We planted drought-tolerant ash trees around the outer edges to provide cooling shade from the Colorado Plateau’s abundant bright sunshine. You can also find dappled shade under the ponderosa pine vigas of the arcade on the north side.

If it is May, June, or July, the Pollinator/Potager Garden will likely be warm, green, and colorful. This is the time of year when the edibles like Hopi or Santo Domingo blue corn are growing rapidly, and the lavender and roses are in full, glorious bloom. You can beat the heat by visiting the Potager in the early morning or late afternoon. Inhale the scent of red roses, blue lavender flowers, and white basil blooms….

Walk through the North entry door. Our Entry Garden was designed by Allan Affeldt with landscape architect Christy TenEyck, and built mostly 2006 – 2008. Before this project, the hotel’s north side consisted mainly of a long asphalt parking lot, with a strip of thirsty Bermuda grass and scraggly non-native Siberian elm trees occupying the space between the parking lot and Route 66. Colter intended a simple driveway to the hotel’s ‘back-door, with native planting and a rock garden extending to Route 66. In the 1960’s though, the Santa Fe Railway gutted La Posada, converted it to their Arizona Headquarters, and paved the north gardens.

Our challenge was to make a welcoming entry. The typical hotel would have left this all as pavement and parking, but we wanted to create a sense for our guests that after leaving their cars they were entering another era; the grounds of a grand hacienda. And we wanted to remove stairs so everything was accessible to everyone. We created a double row of parking across the Route 66 edge, and inserted new gardens between the parking and front door. Now let’s explore the gardens.

Exit the front door and turn right to a patio. On Colter’s plan the patio was very narrow and accessed only from the dining room (now our reception area). In 1930 there were stairs at this (back) door, to a circular driveway, and a little road between west and east entries. Along Route 66 was an area marked as ‘rock garden’. There was no parking here – visitors would have had to park east of the hotel in the staff lot.

We extended the north patio to make it big enough for gatherings. There is a lot of wind in Winslow, typically from the Southwest, but here in the shadow of the building you are protected from the wind and can sit with friends overlooking the entry gardens. Walk across the patio under the shade of Marshall seedless Ash trees, then down the shallow stone steps. Here you find a wooden bridge and a water channel – evoking the safety of a moat – and then you enter the pollinator/potager garden.

Leave the Pollinator/Potager by the corn gate to your east and you are again on the entry walkway. This stone path to the front door showcases arid-adapted, flowering native and non-native plants. Especially prominent in these beds are blue-flowered catmint, a non-native, and blackfoot daisy, a native of the Southwest whose white flowers bloom almost continuously in summertime. You will also find more lavender and rosemary plants in these beds. We brought in lean, quick-draining soils for the plants in these beds and mulched them with small diameter, shredded bark. The bark conserves moisture and helps to suppress weeds. It is also cooler and easier to work with than the original rock mulch that covered these beds.

Now you might ask: what is that camel doing there? The camel harkens back to the Beale Wagon Road that once came by here, roughly following a path that later became Route 66. Lt. Beale, a U.S. Army Officer, was charged with finding a route from Santa Fe New Mexico, to Los Angeles California in 1857, not long after the U.S./Mexico War, when these territories became part of the U.S.A. (Arizona became a state in 1912). Knowing that he had to cross a vast Western desert, Beale chose camels as pack and transport animals. He bought a herd in Egypt and Arabia and shipped them to the Midwest, from whence they made the long trek to California. Their Syrian trainer’s name was Hadji Ali, Americanized as ‘HiJolly’ so that’s what we call the camel. One day Dan Lutzick was in Mexico. He texted Allan to ask if there was anything special he should get. Allan had just read about the Beale Expedition, and suggested in jest: a camel, thinking of live ones. So Dan brought this one back for our garden to tell the story of when camels strolled past in 1857 with the 1st U.S. Army camel corps.

North of the camel we added a cobbled court in the center of the long driveway. This is to indicate the entry walkway, and to get drivers to ‘slow down and take a look at me’ from the Eagles first big hit – ‘Take it Easy’, with the famous line: “Well I’m standing on a corner in Winslow Arizona, such a fine site to see”. The song was co-written by Jackson Brown and Glenn Fry. A few years ago Jackson played the song in a concert on La Posada’s back lawn, but that’s another story. When you look down on this space from the 2nd floor galleries, you can see that the walkway (ramped gently to the front door to eliminate stairs) is in the shape of a Hopi Katsina maiden, with the walkway as the neck and body, the stone circle as her head, and the cobbled rays as her headdress. A Half Moon flowerbed surrounds the entry circle as the necklace for the Hopi maiden. Here you can find: Rabbit Brush, Dianthus, Salvia, Blanket Flower, Desert Willow, Blackfoot Daisy, Rocky Mountain Penstemon, Firecracker Penstemon, Hopi Amaranth, Cosmos, Allium, and Russian Sage.

Today most of our guests enter the walkway and gardens under a historic wrought-iron arch. This once was along the Route 66 parking edge going down steep stone stairs to the street. This was the only ironwork to survive from Colter’s time, so we integrated it our Garden entry to welcome you to La Posada, a tie between Colter’s gardens and ours.

Go down the entry walkway toward the front door turn and turn right (west) through a beautiful gate. All the wrought-iron work at La Posada is the work of John Suttman, and all of it tells a story. This one is called the rose gate because of the floral details. When we bought La Posada this area still had a couple of heritage tea roses. They are still here, and though not fragrant they have an explosion of small short-lived flowers in early summer. Nearby, the handrails of the moat bridge are in the form of pussy willows which grow in the nearby Little Colorado. The Patio gate has baby corn pushing its head through the soil, while the Pollinator/Potager gate has full grown summer corn. The indigenous maize (corn) plants were and are a staple food for both ancient and contemporary cultures.

Through the rose gate is a brick walkway towards the Sunken Garden wall. On your left is a large rectangular well, which we call the grotto. There is a tradition in the middle east and subcontinent of well-gardens – excavated terraces deep to water sources, just as here. La Posada is built over a ground floor of almost 8,000 sq ft, well-lit with windows all around below the ballroom and east wing. To enable public access to this area we needed another stair down under the ballroom, so we decided to create this well garden to bring light and access. We have designed five large guestrooms and a living room under the ballroom, and construction is underway. The grotto will also have a waterfall from the moat above to bring the enchanting splash and oxygenation of falling water, and a Southwestern-style zen garden at the base of the grotto. The grotto rooms are underway, but we’re having a really hard time finding skilled construction workers…

Walk west towards the turquoise blue door that leads into the Sunken Garden. As you pass through the rose gate, notice that the path changes from the Entry Walkway’s random sandstone to this walkway of brick on a bed of fine sand. To the left (south) of the brick path and against the hotel wall is a small orchard of Quince trees. These are the only remaining fruit trees from the initial hotel era. We think that Mary E.J. Colter had them planted in this protected alcove just east of the Sunken Garden in 1930. The trunks and branches of these trees look ancient and twisted. Quinces are a member of the rose family, and were likely one of the first domesticated fruit trees – humans have been cultivating them for at least 4,000 years.

Closely related to both apples and pears, quinces are an important part of Europe’s agricultural heritage. Their distinctive fruits help to tell Colter’s story about a wealthy Spanish/Mexican Don whose sprawling, beautiful hacienda (La Posada) welcomes guests to pause and rest on their journeys across the Painted Desert. In this creative yet historically-based narrative, the Don’s Spanish ancestors brought quinces and other fruit trees with them from Spain to Mexico, planting them in “New World” gardens, like La Posada’s.

Quinces should not be eaten raw. When ripe, their slightly fuzzy skins turn from green to yellow. To make them into jam, you first peel the skins, cut the firm flesh into smaller pieces, and cook the fruit for a while like applesauce, adding pectin, sugar, or honey. La Posada’s quinces also make an excellent chutney and a delicious pound cake. Our chefs use these organically grown quinces to make dishes for the Turquoise Room. When you eat the fruits from these elder trees, you are eating a living history that is both real and imaginary.

Despite their age, La Posada’s quinces are wonderfully productive. Their protected location helps them to avoid having their flowers frozen by the inevitable frosts of late April. La Posada’s own honeybees pollinate their flowers, and we rarely prune live wood from these trees, only a few crossers, root suckers, water sprouts, and sometimes dead branches. We fertilize the roots in both spring and fall with a pelletized organic lawn fertilizer, and water them deeply but sparingly, especially in springtime to delay flowering. Several years ago we planted a living mulch of alfalfa and other nitrogen-fixing legumes beneath their canopies, and placed a bench here for you to sit among the quinces and imagine this oasis being planted more than ninety years ago.

Follow the brick pathway through the blue doorway into the Sunken Garden. The well-worn wooden benches of the gatehouse are a good place to sit and enjoy the cooling, refreshing shade during hot weather. From here you can listen to the many different song birds who visit the Sunken Garden, especially during the growing season.

This is a classic Mediterranean walled garden – a small green, enclosed oasis surrounded by the larger desert oasis that Colter imagined as La Posada and its gardens. In late winter the first tiny leaves appear on the honeysuckle vines; and ends here last, in late Autumn, when the last yellow petals fall from frozen Maximillian sunflowers. The first purple and yellow crocuses have been known to flower here in late January or early February. In between, the gardens rest and sleep, saving energy for the first growth of spring.

The Sunken Garden is La Posada’s warmest microclimate. On a raw, windy day in winter, the rock bench below the honeysuckle arbor on the Sunken Garden’s south side is the only spot in the gardens where one can find warming winter sunshine. The Sunken Garden is especially beautiful in spring, summer, and fall. The bluegrass and bermuda lawn in the center is surrounded by beds of perennial flowers and shrubs, surrounded by a path of crushed rock. Turn left from the Guard House toward the stone terrace and make a loop through this lovely space before heading back through the Turquoise Door to continue your tour.

If you walk around the Sunken Garden during the growing season, you will encounter a vivid flowering biennial called the hollyhock. Like sunflowers, hollyhocks flower on tall, upright stalks, but they will usually display multiple flowers on a single plant, sometimes in more than one color. La Posada’s hollyhocks are mostly white, red, pink, burgundy, or black. The hollyhocks hybridize freely and spread themselves from the hundreds of seeds that come after the flowers. We love their large, brightly colored, pollen-rich flowers, and admire their remarkable hardiness. They require very little water, but will use it if available. Hollyhocks and many other plants in the cotton family (like our native globemallows) seem especially happy here in our gardens.

Other plants in the Sunken Garden’s low and raised beds include: Cypress, Mulberry, Spirea, Lead Plant, Moonshine Yarrow, Honeysuckle, Dolly Madison Roses, China Roses, Jasmine, Flycatcher Honey Suckle, Yellow Currant, Viburnum, Maximilian Sunflower, Sweet Pea, Primrose, Tulips, Daffodils and Virginia Creeper. Boston Ivy covers the wall on the patio area, while the pots are filled with: Swiss Chard, Kale, Spinach, Tulips, Daffodils, Mums, Pansies, Sage, Jupiter’s Beard, Aster, Grasses, Snapdragons, and lilies. Tina’s Kumquat is sure to make an appearance in the warmer months. You might also see lavender, chocolate flower, prostrate rosemary, wild and hybrid tea roses, crocuses, and scented hyacinths (in springtime), snowball bush, echinacea, Arizona columbines, New Mexico penstemons, and red salvia. Many of these are natives, and many are not. Most are xeric, which means drought-adapted, needing relatively little water to thrive.

Some native plants love water, like lead plant (Amorpha fruticose). This large shrub grows in riparian areas of the southwest. You can find one here growing to the east of the shallow pond at the south end of the lawn, just below the waterfall. In May, this riparian shrub is covered by masses of long purple flowers. Bees, butterflies, and other pollinators love these flowers. When the Sunken Garden was reimagined in the 1990’s – based on historic photographs and Colter’s original plans – we designed to attract and benefit pollinators like butterflies, hummingbirds, and honeybees. We also chose plants with attractive scents like rosemary, chocolate flower, lavender, roses, and honeysuckle vines. The Sunken Garden’s sweet scents can be quite intoxicating when in flower.

Several features here are worth noting. This was Mary’s most formal garden, with a classic water axis from the lion fountain pouring water over a huge petrified wood stump on the south to a small pool below the stone terrace. In the redesign, Allan enlarged the lion pond, added raised beds on the west and north side of the lawn, and a raised pool at the edge of the terrace, with three roof tiles to pour water into the pond below. The ceramic roof tiles that create an edge between the grass lawn and the planting beds surrounding it are the same reddish-brown tiles that cover La Posada’s roofs.

Whether you enter the Sunken Garden from indoors via the Cinderblock Court, or from outdoors via the Turquoise Door/Guard House, you encounter a special place, a protected sanctuary from the desert’s sun, heat, cold and wind. As you walk back down the steps from the stone patio onto the gravel path, consider the vertical effects in this space. Like a terraced mountainside, this place has many levels, and is more complicated than it seems. When you enter the garden from the hotel, you walk down a short flight of steps to the patio, and then down again to the lawn: it is the walking-down that makes this a “sunken” garden, set below the first floor of the hotel.

Back through the sunken garden guard house turn left toward Route 66. To your right there is a gravel walk around a crabapple tree. The form of the little path here is an ankh, an ancient Egyptian protection symbol (and an early form of the cross). Within the ankh path is a Peace Pole, with the words ‘may peace prevail on earth’ in four languages: English, Spanish, Hopi and Navajo – the four cultures that most influenced our region. Allan Affeldt had an illustrious history as an international peace activist before he began saving important buildings in the southwest.

Most of the plants around the Ankh are members of the rose family, which includes quinces and apples. The base of the crabapple is surrounded by more lavenders and small rose bushes. Depending upon the season, you may see dozens of small, wrinkled red “berries” on these roses. These are rose hips—fruits that develop from the roses’ copious flowers. Rose hips are edible and are high in Vitamin C. The Turquoise Room has made excellent teas and jellies from them.

Wild roses are much happier than domesticated roses in this garden; they do fine with either very little water or with a lot. Unlike domesticated roses, these produce hundreds of small, short-lived flowers. You will also see a few young lavender plants here. These culinary and medicinal varieties were acquired from our friends at Red Rock Lavender Farm in Concho Arizona, near the White Mountains. We chose roses as the theme of this area to support Colter’s backstory about how Spaniards brought quinces and other parts of Europe’s agricultural heritage (wheat, apples, honeybees) to the Americas, as part of the “Columbian Exchange.” The rose also played a role in the introduction of Spanish Catholicism to the indigenous peoples of Mexico and beyond. When an Aztec Indian named Juan Diego was visited by La Virgen de Guadalupe in 1531, in a place that was especially sacred to the Aztecs, she gave him roses to take to church authorities, as proof of her presence in the Americas. This miraculous visitation happened in a season when roses never flowered! The Catholicism that grew out of this encounter was a synthesis of European and indigenous American elements. The rose thus symbolizes the mixing of biology and culture that has been especially powerful in Latin America and the American Southwest. This mixing or mestizaje, also inspired Colter and our vision of La Posada as a special place within a larger story of the encounter between the Americas and Europe, and is one of the reasons we included elements in our garden design whose origins are in the Hopi and Navajo cultures of our neighbors.

Walk westward past a majestic Fremont Cottonwood and following the same general direction and path of the Beale Wagon Road and Route 66. The hotel’s two story west wing will be on your left, with parking on your right. Unlike the Wild Rose Garden, the North Walkway does not focus on a single plant family. Another even larger Cottonwood once overlooked the north end of the Sunken Garden, but in old age its great branches started follow in the 1990’s and it had to be cut down. Remarkably, this Cottonwood has grown three new trunks from its apparently dead stumps. We affectionately referred to these as the Tres Amigos, named after Tina, Allan, and Dan who saved La Posada. Their work here grew from the strong roots of another trio – Mary Colter, Fred Harvey Company and the Santa Fe Railway. A family of friendly skunks inhabit the base of these trees. Sometimes you may see them ambling along. Once they strolled through the Cinderblock Court on their way from the south lawn to the Sunken Garden!

This area receives no winter sun and is exposed to Winslow’s prevailing southwest winds, especially on the western end. By experimenting we see that xeric, flowering perennials like penstemons and whirling butterflies are happy in these beds, while low, sprawling native four o’clocks and lemonade sumacs can handle the strong winds at the west end of this garden. Look for Goodding’s Willow, Sumac, Apache Plume, and Hollyhock along the pathway, along with Wild Rose, Rabbit Brush, Rocky Mountain Rose, China Rose, Tea Rose, Chocolate Flower, Lavender, Rabbit Brush, Chaste (Vitex) tree, Catmint, Russian Sage, Blanket Flower, Rosemary, Missouri Evening Primrose, Potentilla, and tall Flycatcher Honeysuckle growing at the base of the hotel’s west wing.

During the Railroad Era (1930-1957), La Posada and its gardens were supplied with surface water rather than groundwater. In those days, the City of Winslow’s primary water supply was nearby Clear Creek, which flows into the Little Colorado River just east of town. Both Clear Creek and nearby Chevelon Creek begin on the Mogollon Rim south of Winslow and are fed by perennial springs, winter snows, and summer rains. During the early 1880s, it was the confluence of the Little Colorado River and its tributary Clear Creek that caused the railroad to create a stop on the tracks. Steam engines pulling trains west to California from New Mexico and points further east stopped here to “refuel” with the abundant waters of these two desert watercourses. This stopping place on the rails eventually grew into the city of Winslow. Now our water comes from wells, ever deeper. This groundwater generally has a higher mineral content than either rain or surface water, which leads to challenges of increased soil salinity in arid environments like ours.

As you near the western edge of the Brick Walkway, look to the right (north) across the parking lot to another important area of the gardens. Prior to the creation of our new Entry Gardens on the hotel’s north side, this area between the parking lot and Route 66 (also known as 2nd Street, the main thoroughfare that passes La Posada) was primarily of bermudagrass lawns and Siberian elm trees. Now it is a showcase for many of the native plants of the Southwest. Some of the species you will find in this hardy garden are saltbush, sand sage, apache plume, banana yucca, chamisa, and cliffrose. Also here are some mostly native trees, including juniper, oak, and Marshall seedless ash – a deciduous tree that casts much appreciated shade in the desert’s bright sunshine.

The clay soil in this area was not well-drained enough to support xeric native shrubs, so we added quite a bit of sand and compost during construction of the Entry Gardens. We used drip irrigation to get the plants established, but now turn the drips on only occasionally, since these natives are well-adapted to the arid Painted Desert. This garden is also mulched with chunks of native rock, which helps to conserve soil moisture and to inhibit weeds.

On your north (right) at the end of the brick walkway is a lovely stone arcade with viga roof. We built this in 2008 to create a separation from the parking area and the gardens. The arcade also forms a visual N/S axis with a statue of St Francis in an alcove by the railroad tracks off to the south. We have planned a large heritage rose garden fronting the arcade. During the Victorian Era in Europe and the Gilded Age in America (mostly the late years of the 19th century), grand estates nearly always had major rose gardens. A few of these great Victorian Rose Gardens survive, like at the Huntington in San Marino CA (also built by a railroad magnate). We hope to build ours soon!

To the west of the hotel is a very historic and ecologically important part of the gardens: a ring of mostly Cottonwoods around a large oval of mixed bermuda and bluegrass. The Cottonwood Grove is central to Colter’s vision of La Posada as an oasis in the desert. Water-loving Cottonwoods are dominant features of the Southwest’s riparian areas, where they provide shade, shelter, and food for other plants, insects, birds, and humans.

Past the West Stone Arcade a crushed granite walkway continues our tour along the north edge of the Cottonwood Grove. Follow this granite path west towards the faux stables. On your left are high honeysuckle bushes, with yellow currants growing behind. These currants nearly always produce fruit, and are highly prized by the many different bird species that visit La Posada as they stop in the gardens for food, water, and shelter on their migratory paths. Continue along the path and you will see a bed of indigenous and edible Jerusalem artichokes. Just beyond this on your left is one of the oldest, largest trees in our gardens, an elder Rio Grande cottonwood. A younger offspring of this old “alamo” (Spanish for cottonwood) is growing from one of its thick surface roots.

These trees were planted when the hotel was built in 1930. Three of the grove’s elder cottonwoods died suddenly in 2002. The roots couldn’t grow fast enough to reach the watertable as it dropped during our worsening drought, and we couldn’t get enough city water to keep this grove alive. We negotiated a permit for the only well in city limits to keep these majestic survivors alive with flood irrigation. That any of La Posada’s old cottonwoods have survived is testament to the hard work and dedication of local volunteers who dragged hoses across Route 66 to the gardens during the years after the hotel was closed and the Santa Fe Railroad turned La Posada into offices.

We have been planting young cottonwood, mulberry, and other shade trees in and on the edges of the Cottonwood Lawn for the past decade or so. At first we tried some younger saplings of diverse species, including several dozen narrowleaf cottonwoods that we obtained from Flagstaff High School, but found that few of them could survive Winslow’s difficult growing conditions. More recently we have been planting much larger cottonwood specimens with larger canopies and thicker trunks. These trees are doing better, and we hope that the many new trees that we are planting in the Cottonwood Grove and other areas will be large and healthy by the time the surviving trees from the 1930s have gone back to the earth.

Continuing on the pink granite path, beyond the old Alamo and other, younger cottonwood trees, you may notice a long, thick green vine growing on top of the fence to your right by the parking area. This is Silver Lace Vine, a plant that does exceptionally well here, along with red-flowering trumpet vine. If it is summertime, this vine will be in full bloom, covered with small white flowers and pollinating insects, like honeybees and bumblebees.

The Cottonwood Grove is perfect for birdwatching. A few of the types we’ve seen are: Western Tanager, Eastern Flycatcher, Bullock’s Oriole, Goldfinch, Warbler, Turkey Vulture, Golden Eagle, Red-tailed Hawk, Harris’s Hawk, American Kestrel, and even the occasional Roadrunner. Our hummingbirds love the nectar-rich flowers on the trumpet vines.

The trees in and around the grassy area include: Arizona Sycamore, Mountain Ash, Desert Olive, Vitex, Mulberry, Elm, Cottonwood, New Mexico Locust, Honey Locust, Black Locust, Russian Olive, and White Poplar. Planted among the trees are: Rosemary, Yarrow, Yerba Mansa, Iris, Wild Rose, Wax Currant, Black Currant and a variety of wildflowers.

As the granite path along the north edge of the Cottonwood Grove comes to an end, you can see a long rambling stone and wood structure. This was the gardeners house and tool sheds. Colter’s original design for the gardens shows a greenhouse and vegetable beds here. Unfortunately, the Great Depression hit while the hotel was being constructed, and many of the features that Colter planned were never built. A steam-heated greenhouse was built in the 1930’s but only lasted a few decades. Look closely at the circular stone wall to your right and you will notice a series of portholes. This wall replicates defensive features from Fort Brigham, a Mormon settlement built just north of Winslow along the little Colorado River.

This part of the garden is not protected from wind but these local sandstone walls and bright sunshine create a warm, nurturing microclimate, even in wintertime. Heat absorbed from the sun during the day is slowly released as solar energy at night, creating a narrow band of extra warmth loved by heat-seeking vegetables like squash, basil, and tomatoes. We have been experimenting with using cold frames along the this wall. By enhancing the wall’s passive solar effects we can grow cold-tolerant plants like lettuce, kale, and chard in these cold frames, even in the dead of winter. Overnight temperatures can fall to zero or lower in January, but the green plants inside the cold frames rarely freeze. In summer, when the heat really arrives (usually in late May and peaking in June) we open or remove the cold-frame tops, and grow heat-loving chiles and other plants. During wintertime, you may find soil-improving cover crops like foenugreek or winter rye grass growing in these beds, along with cold-tolerant plants like garlic and onions. We are constantly working on improving and feeding our soil, giving back to the earth what the plants take as part of our organic approach to gardening. Other plants here are Hopi Amaranth, Hopi Corn, lavender, winter and summer squash, pumpkins, gourds and loofa.

Between the west wall and the cottonwood grove you will find a wellhouse and a milpa – a little farm developed by our gardener Manuel Contreras. Autumn leaves from the cottonwood trees become a fertilizing mulch during the wintertime, protecting the soil from wind erosion. Manuel’s milpa has been very productive, growing Mexican elotes (ears of corn) for making nixtamal, the processed dough that is shaped into corn tortillas, the daily bread of Mexico and the rest of Latin America. Manuel also grew several kinds of beans, pumpkins, and squash in the milpa, along with nitrogen-fixing scarlet runner beans, which go vining up the corn stalks and create red and white flowers, loved by the hummingbirds. These plants—corn, squash, and beans–are the three sisters of the Tarahumaras, Cherokees, Hopis, Navajos, and other indigenous agriculturalists. They work together in mutually beneficial ways, the beans providing nitrogen for the nitrogen-loving corn; the corn providing scaffolding for the bean vines, and the squash leaves providing cooling shade for the roots of the corn, also helping to suppress weeds. Large yellow squash and pumpkin flowers also attract beneficial pollinators, like honeybees. Squash blossoms (male only, since the female flowers produce the fruits) are also a summertime delicacy in The Turquoise Room.

Next to the Garden sheds is a large arched gate with two ancient swinging doors. In a grand hacienda such a wall and gate was a common feature marking the end of the estate and the beginning of the fields. Beyond this gate there were once two tennis courts. Over time, the roots of Siberian elm trees have buckled and broken the concrete. A softball field with a backstop was also located out here, in the northwest corner towards downtown Winslow. The gated arch is in what would have been deep center field. During La Posada’s early years this area was a kind of public space. Historic photographs show that events like band concerts once took place here, and at Easter Winslow families would cue up for a grand easter egg hunt. This area is not on the tour but you are welcome to take a quick look through the gate. We have a top bar hive of gentle honeybees living in this area, along with large debris and compost piles. Otherwise this acre of land is not in use. We plan to rebuild the tennis courts.

Continuing south toward the railroad tracks, you will see a small square wooden structure on top of a low concrete pad. This is La Posada’s own irrigation well, the source of the groundwater that we now use to take care of the Cottonwood Grove. In summertime, you will likely see a long two-inch diameter blue hose coming out of the well house. If we’re watering, the hose will be gushing about 75 gallons of cold water per minute onto the soil, most of it percolating back down into the ground. La Posada’s well uses electricity and a pump to bring up water from the Coconino Aquifer. Our well is 300 feet deep; the city’s wells are several hundred feet deeper and are located a few miles to the southwest of town. As we anticipated, digging an irrigation well was a major project, costing thousands of dollars and many hours of work. We obtained the necessary permits, hired a driller, purchased and put in the necessary infrastructure, and struck water not far beneath the ground. Winslow and La Posada are located in the Little Colorado River Valley, so our well water is abundant, but the quality is marginal. The City’s water is relatively salty and rich in minerals, but our water is even more so. We can use our well to provide life-giving moisture to the Cottonwood Grove, but we cannot use the water for our automated lawn sprinkler systems or drip systems. The water is literally so high in minerals (especially salt) that it burns the leaves of many plants or eventually prevents them from absorbing water through their roots. Like the gardens themselves, the irrigation system is a work in progress. We know that water quality and quantity are major issues that will continue to confront us everywhere in the Southwest for decades to come. To survive and thrive, La Posada’s Gardens will continue reducing the amount of water that we’re using by planting more native and xeric plants, by reducing thirsty lawn areas, by automating our irrigation systems. Using lawn sprinklers only at night when evaporation rates are much lower, and using organic fertilizers and mulches, we can create the healthy, living soils that help plants thrive in prolonged drought conditions.

Continuing around the cottonwood lawn you will find a gate to the tennis courts, and then a little fruit orchard in the Southwest corner. We have tried a variety of fruit trees, such as: Pear, Plumb, Apple & Cherry. This is a hard place for trees, as everything here is buffeted by the Southwest winds. There is a little hippo bench for pondering the gardens and looking back to the hotel. Adjacent to the orchard is a stone building with a turret. This was used by the Santa Fe Railway as a workshop and guard tower for the trains passing through. There used to be a steam radiator here – imagine the long cold nights of winter in the 1930’s! The sheds are unused now but we plan to make them a feature of the Strawbale Maze.

Colter’s original site plan indicated a ‘maze’ here, but as far as we know nothing was ever built. Unlike a labyrinth – which has one path to the end or object – a maze has many dead ends. A maze was a common feature of classical garden designs going back at least to Roman times, where it was seen as a metaphor for our many choices in life. The dreadful Minotaur of course lived in a labyrinth, from which there was no escape. Several Southwest peoples also had maze and labyrinth traditions. The Mojave Indians made huge labyrinths and mazes composed of rows of stones marking meandering paths in the desert. Hedge mazes were all the rage in the Victorian era; play places for both for children and for lovers. They are most commonly built from living yew, boxwood or holly. Allan loves mazes and always wanted one, but knew it would be too hard to create and maintain a living maze in the desert. In pondering this desire and dilemma, he hit upon the notion of building a maze from strawbales, and that has been our tradition for two decades now. Well-strung bales are quite durable, but every couple of years we have to get new bales and build anew, each time with a few changes in the design to keep our guests guessing. We were sold a batch of bad (loose) bales in 2021 for the last rebuild, so we will need to start over soon. The golden-hued maze is especially lovely in the late afternoon sun.

Continuing toward the hotel you will see a statue in a raised niche in the low stone wall by the tracks. Local legend has it that a lot of stone masons were brought from Italy to help build Roosevelt Dam to the south. When that project was done, Colter brought them to La Posada to help build the long stretches of stone walls all around the property. Throughout the walls are various symbols, from a star of Texas (where first manager Omar Dooms came from) to the niche here for St Francis to watch over all living things. We have never seen a picture with a statue here from Fred Harvey days, but imagine there must have been. Further east is the South Lawn. Grass in the desert is an extravagance, but was used by Colter to suggest to guests arriving by train that were entering an enchanted oasis. Within this lawn you will find a small stone platform with an ornate wishing well. The wishing well shows up in piles of period photos. Everyone wanted a picture with the well and hotel behind. Sometimes people stood in front or behind, but often they were on top of or even inside the well! Unfortunately, the wishing well was auctioned off in Albuquerque in 1959 when the hotel was closed – like virtually everything else that could be removed and sold. The auction records describe it an Italian antique, already ancient when La Posada was built. We thought it was an important element of the garden, so we gathered historic photos and shared them with our neighbor John Suttman, who designed and built this version based on the original.

Continue to the south hotel doors within the arcade. La Posada was built by the Santa Fe Railway in 1929 for travelers coming through the Southwest by train, so the front door was here – facing the railroad tracks. In the 1930’s there were several passenger trains stopping in Winslow every day, with excited passengers getting off for a Fred Harvey Meal in the Turquoise Room. Now each day there is only the Southwest Chief – one passenger train going east and one west, on the Route between Chicago and Los Angeles.

In the 1930’s train passengers would come and go through the depot, but for decades now they have come straight from the train platform to the door of the hotel, so we built a new entryway for them. There are two raised brick platforms with shaded patios and rocking chairs separated by the original concrete walkway. When Allan and Tina bought La Posada there was a demilune curb between the train platform and walkway, so we designed the patios to follow this pattern. Between the patios is John Suttman’s magnificent Train Gate. Look closely and you will find all kinds of railroad imagery in the wrought-iron: wheels and pistons and spikes. This is surely one of the finest pieces of metal art in the Southwest, and a fitting transition from the rails to the magic of La Posada. Along the entry walkway there is a huge petrified wood stump, vitex/chaste plants and some ornamental pomegranates. These pomegranates don’t have fruit, but in the late summer they will be filled with deep red flowers that look like the frilly dresses of flamenco dancers. Once there was also a huge meteorite from nearby meteor crater. It was not part of the 1958 auction so it was surely stolen from the property sometime during the long decline of office use between 1960 and our purchase of the declining property in 1997.

Just east of the entry walkway is a large lawn centered on a flagpole. The pole is not part of the original garden plans and was added during the office occupancy. We added mulberry trees here to provide some shade for the arcade overlooking the Turquoise Room. One very old cottonwood tree in the southeast corner survives from the original hotel days, along with a row of Juniper trees that put out lots of pollen in late summer. The rustic fence of wooden pickets between stone piers is original, though much of the wood has had to be replaced. We added a second masonry wall for added safety, to make sure our guests know where the hotel property ends and the railroad property begins. Only AMTRAK passengers are allowed on the railroad platform, and only when the train is stopped on the platform!

Continue east along the arcade past the Turquoise Room toward the depot. Much of the flagstone walkway here was destroyed through decades of deferred maintenance and standing water from rains, so we added this masonry seat wall and repaired the stone.

As the building ends look left. In the 1940’s the railroad did a small block addition here. We called it the ‘Spam Room’ because it was used to make spam sandwiches around the clock for thousands of soldiers who stopped at La Posada for a meal, riding the rails to the raging war in Europe. During World War II tables set up on the lawns and as many as 3,000 meals a day were served at La Posada. In the early 2000’s we would occasionally meet a veteran returning to reminisce about their lost friends, and the Harvey Girls and grand service they got here on their way to war. The contract to feed troop trains was the last big business for many railroad hotels. After the war, train travel was increasingly replaced by highways and automobiles. Nearly all the great old railroad hotels closed, and most of them were demolished in the 1960’s and 1970’s.

When Allan and Tina bought La Posada the spam room was part of the railroad offices, so it became office space for the Turquoise Room. On the original garden plan, the east side of the property was not developed except for parking. The railroad didn’t need truck deliveries for the restaurant as we do now, and most of Fred Harvey’s food came by train. The business has changed quite a bit!

Now we have lots of guests who would like to eat outside, but our strong Southwest winds make the arcade too difficult to serve meals. To meet this need we have designed a new patio immediately east of the dining room, surrounded by kitchen gardens where our chefs can grow herbs and other edibles for the restaurant. We have been experimenting with raised strawbale beds here and hope to build the new patio where the old spam room was. The beds are also used as “test” gardens for tree and shrub nurseries. Many trees, shrubs and herbs have been transplanted from here throughout the gardens. What’s growing in the Chef’s Beds? Onions, chives, garlic chives, lemon balm, oregano, peppermint, chocolate mint, pineapple mint, rosemary, lavender, thyme. -Summer crops: tomatoes, beans, peppers. -Trees: Granny Smith apple, Bartlett pear, Dwarf peach, Apricot, and Desert Olive. -Flowers and shrubs: Indian Rice Grass, Aster, Shasta Daisy, Day Lily, Globe Mallow, Fleabane, Butterfly Bush, Butterfly Milkweed, Marigold, Spirea, Fern Bush, and Rabbit Brush. Our biggest challenge – like everywhere – is just finding workers: there isn’t a single general contractor in Winslow who does small projects like our patio or grotto rooms, and dedicated gardeners are hard to find. We are so grateful for the crew we have, but wish there were more! Maybe you know someone who would like to volunteer for a season or move here?

Our lovely train station was built in 1929 as an integral part of the hotel complex. The waiting room here is the largest in Northern Arizona, which speaks to Winslow’s importance as a transportation hub in the early 1900’s, much more important than Flagstaff or Sedona at the time. AMTRAK leased the depot for its guests when BNSF offices were here, but nobody was taking care of the building. When we reopened La Posada we noticed that AMTRAK passengers were using the hotel lobby as their waiting room instead of the depot. Of course they did! – we had comfortable chairs, a nice restaurant, live music in the evenings, clean bathrooms. So Allan made a deal with AMTRAK for their guests to use the hotel as waiting room, and we got back use of the depot. Allan’s plan was to restore the depot as a museum to explore the art and culture of the Santa Fe Railway/Route 66 corridor through the Southwest. Plans, permits and raising more than $2 million for the depot renovation took a few years. We needed more exhibit space, so we designed an additional gallery to the east. We acquired remarkable objects including the Hubbell-Joe Rug (the world’s most famous and largest Navajo weaving, 1930-1935, 22 x 36’!); the original 1950 Santa Fe Railway pleasure-dome railcar, which included the original Turquoise Room; the argosy trailer James Turrell lived in and worked in when designing Roden Crater. We opened the renovated museum in 2019 and have big plans for the future!

The Santa Fe Railway didn’t develop the east grounds of La Posada, except for some parking and one curious experiment: In the 1940’s and ‘50’s there was a bandstand here, home to the Santa Fe Railway All-Indian Band. Composed entirely of members from a dozen Southwestern tribes and nations, the band lasted until the 1950’s when La Posada shut down. They played mostly marching music and traveled around the country, including to President Eisenhower’s inaugural parade!

North of the depot/museum where the bandstand once was, we created a walled enclosure with three parts: On the west side is the dining terrace and kitchen gardens. Facing the museum will be a sculpture garden and lavender field. East of the museum will be a vineyard, with a Turrell Skyspace at the far end. It will take some years, but will be quite fabulous! Beyond the museum garden is our solar field, installed in 2009. This nearly ½ acre of panels is the largest private solar field in Northern Arizona, and provides most of the power for the hotel – a major investment in support of our environmental values.

Thank you for being our guest, and for taking this stroll around our gardens. We are grateful for the work of so many to create, care for and grow these gardens – Mary Colter and the Fred Harvey Company who first created them, the Santa Fe Railway whose vision and money paid for them, the Gardening Angels and local volunteers who kept them alive, our master gardeners from Patrick Pynes to Char Tomlinson who brought them back with their years of love and effort, and the designers of our modern gardens Kristy TenEyck and Allan Affeldt. We are honored to have you as our guest, and hope you will tell your friends and family about this special place.

Allan Affeldt and Tina Mion, Owners

Char Tomlinson, Master Gardener

Kristi Ulibarri, General Manager

Daniel Lutzick, Special Projects

and the team at La Posada and the Turquoise Room

“THE RESTING PLACE”

La Posada is so much more than just a hotel and offers many intimate and peaceful environments both inside and on the grounds of the hotel.